In Robert Mitchell’s “Bioart and The Vitality of Media”, particularly in the section ‘Affect and Framing I: Readymades’ in his chapter ‘Affect, Framing, and Mediacy’, he provides a useful introduction to vitalist bioart which appears to work well with our cabinet project. Mitchell states that “understanding the experience of bioart in terms of affect also allows us to focus more closely on the ‘artistic’ conditions of possibility of contemporary vitalist bioart-that is, the ways in which recent vitalist bioart depends upon twentieth–century techniques of framing objects and experiences as ‘art’ in order to prolong experiences of affect. This is an important aspect of vitalist bioart, for it is intended not simply to produce but also to prolong experiences of intensity. This goal distinguishes recent vitalist bioart from other experiences which may produce affect through a sense of becoming-a-medium…Vitalist bioartworks, by contrast, seek to extend the experience of affect rather than allowing it to resolve into situated perceptions and cognitions” (77). In order to fully understand what is meant here by Mitchell and to form some sort of connection with our cabinet project, a definition of vitalist bioart is useful. Mitchell says ““Vitalist bioart is… primarily exploratory and experimental: that is, rather than seeking–or seeking to safeguard–the ‘meaning of life,’ vitalist bioart instead explores what life can do” (32). Also in this section, Mitchell highlights a form of bioart that arguably our cabinet project falls into. “Readymade” is a term coined by Marcel Duchamp to describe the practice of reframing industrially produced (i.e ‘readymade’) consumer items, such as bicycle wheels, bottle-drying racks, and urinals (or in this case, a industrial arcade cabinet), within the space of the art gallery (78).

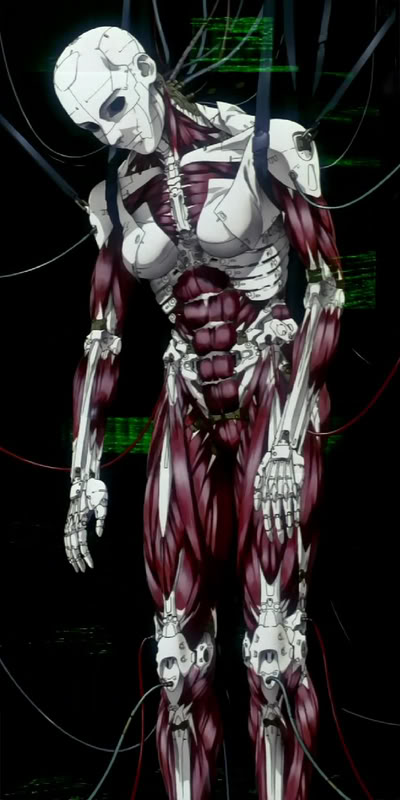

Our project essentially will exist as a readymade installation of vitalist bioart. As Mitchell clarifies, “the readymade suggests, does not preexist its exhibition in an artistic space; rather, the exhibition of something establishes its (possible) status as art” (78). While it satisfies the condition externally of a readymade, it functions much more than simply an object to be viewed. Indeed, the cabinet serves as a housing for a more intricate and interactive application (or perhaps art as it is being exhibited within the confines of an art gallery). While our cabinet itself is not actually a living, breathing, biological instalment, certainly an argument can for our “I Am Nobody” application contained within the cabinet. As it presents a way in which the body can be ‘altered’, more specifically, mediated, an exploration surrounding an aspect of biology is certainly on display. Our cabinet presents the head of a human, extended into the cabinet, and remediated through the interactive participation of those who engage with the cabinet. Whether or not gallery goers will be amused, view our cabinet as art, or just be down right annoyed with our installation remains to be seen. What we certainly hope to accomplish is to get participants thinking critically (otherwise, we would not be doing our job).