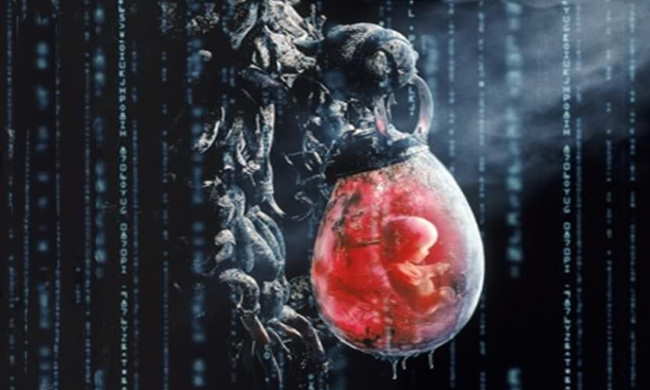

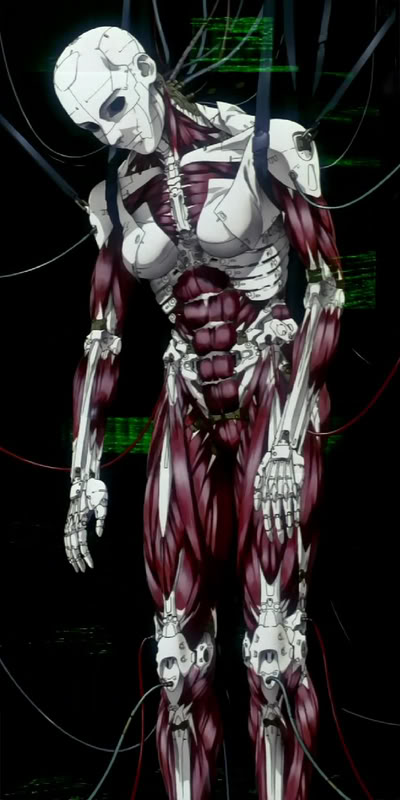

Here are some shots from the filming of Nobody, using Cam as the model for our cyborg. This is also some of the first uses of our new studio/workshop/class space for the Critical Media Lab, at 158 King St W in Kitchener. Equipment used: Sony HDR-FX1000 camera w/spotlight attachment, and Macbook Pro running Final Cut Pro. We shot original footage in full 1080p resolution (1920×1080) and rendered it in post-production for implementing in the Flash game framework at 640×480.

Archive for March, 2011

Anne Balsamo’s “Forms of Technological Embodiment: Reading the Body in Contemporary Culture” introduces us to a concept that is interesting to consider in relation to our cabinet project. She introduces “The Repressed Body” with an elucidation of the concept of repression:

“Repression is a pain management technique. The technological repression of the material body functions to curtail pain by blocking channels of sensory awareness. In the development of virtual reality applications and hardware, the body is redefined as a machine interface. In the efforts to colonize the electronic frontier-called cyberspace or the information matrix-the material body is divorced from the locus of knowledge. The point of contact with the interior spaces of a virtual environment-the way that the computer-generated scene makes sense-is through an eye-level perspective that shifts as the user turns her head; the changes in the scene projected on the small screens roughly corresponds with the real-time perspectival changes one would expect as one normally turns the head…for the most part the material body is visually and technologically repressed” (228).

Balmaso’s notions of repression and ‘the repressed body’ are interesting when one turn’s their attention to Nobody. The appearance of this character is repressed on two levels. On one level, it exists only through a digital medium afforded by our cabinet. On the other, its function is repressed to the level of being almost entirely dependant on the input of participants with the cabinet. In essence, one might come to understand Nobody as a “repressed body”. Certainly this concept is on to think about in relation to our project as it appears Nobody may in fact represent one of Balmaso’s important concepts.

Reading Anne Balsamo’s article entitled “On the Cutting Edge: Cosmetic Surgery and the Technological Production of the Gendered Body”, many great points were raised about the modifications that women undertake with the desire to alter their outward appearance or even in an attempt to defy the aging process. As I read this following her previous article which mentioned bodybuilding, it got me thinking.

In “On the Cutting Edge”, Balsamo asks “How is it that men avoid the pejorative labels attached to female cosmetic surgery clients” (219) and furthers this question with the statement: “So whereas ‘being a real man requires having a penis and balls’ and a concern with virility and productivity, being a real woman requires buying beauty products and services” (220). Her questions and statements seem rather odd after have just discussed the phenomenon of bodybuilding in her previous article.

In the male bodybuilding realm (but not limited to only male bodybuilding), we find two schools essentially. “Natural bodybuilding” is where essentially the transformations done to one’s body are the result of diet, training, and supplementation that have no effects of hormones within the body. Sometimes, supplementation outside of multivitamins and protein are forbidden (products like Creatine or Nitric Oxide precursors). Think of it as “a farm boy with a gym membership” or “Wheaties and Spinach”. The other school of bodybuilding is essentially no holds bar. Steroids, human growth hormone (HGH), and almost anything under the sun are legal and used in order to achieve the maximum potential of ones genetic makeup. Among the lesser known and often frowned upon enhancements bodybuilders can acquire are also cosmetic options including calf implants, glute implants, and the injection of a product known as Synthol. The implants are essentially exactly what one thinks when they hear these: implants in order to enhance the look of those parts. Synthol is a lesser known product that takes bodybuilding to a whole new level of aesthetics (if done right). It is essentially oil that is injected into the facia tissue of your muscles. It fills them and expands the muscle, giving it the appearance of strength with nothing more than oil occupying the space. You do not gain strength from it and its effects do wear off over time; the benefit is purely aesthetic. Often used to balance out unsymmetrical body parts (arms, legs, chest and back), if used right, the results are almost unnoticeable to the naked eye. Others have gone too far. For more information about these cosmetic options for bodybuilders, visit: http://www.bodybuilding.com/fun/ronharris8.htm. This website also contains a lot of other scholarly supported research in an attempt to distil truth in an otherwise confused world of exercise science.

What can be taken away from this insight is that contrary to Balsamo’s earlier statements, men do not in fact avoid the pejorative labels attached to female cosmetic surgery clients. While these aesthetic enhancements are found primarily in the bodybuilding world, they are by no means confined to it. The recent rise in bodybuilding supplementation and the attention to aesthetic male physical appearance over the last decade has put an increasingly large amount of pressure on males to meet these standards. Supplement companies promise the “next best weight loss pill” or “the pre-workout formula that will deliver insane lifts” all playing off of the desires held by many males to obtain more ‘masculine’ physical traits. No longer does “‘being a real man requires having a penis and balls’ and a concern with virility and productivity”, it also requires a six-pack, a nice butt, strong arms, and a laundry list of other demands. If someone cannot put in the hard work or simply does not have the genetic disposition to achieve the desired aesthetics they want, never fear, they can buy their image. Buyers beware, for these purchases do not come without public criticism. Buy a new buttock and you might be questions about whether or not you had to replace your old one because it had a crack in it. Obtain Synthol injections and risk being labelled a “juice monkey”. It may not have always been this way, but a survey of the “ideal” male figures will undoubtedly turn up results where these men possess these traits to a relatively high aesthetic degree.

One of the main points of concern for David Wills is that technology isn’t living up to its promise of making our lives better but is having the opposite effect of making our lives more difficult by increasing the speed of things without increasing the payoff. This attachment to our gadgets and our lives is experienced in some way by nearly everyone who engages technology. Having email on our smartphones is great, except that it keeps us plugged in at all times and most people don’t ever switch off. This growing trend of constant connection and ultra-fast technology is a concern for Wills and our cabinet project is an attempt to directly engage this idea. In our project I am Nobody, the user is confronted with a human image that glitches on a continuous loop making it appear as if it is looking out of the cabinet and around the room. When the user presses a button they are given either a piece of a sentence from literature regarding embodiment (a 1 in 17 chance) or a cue from the machine about their error. We have included a set of replies from the machine that indicate process, words like “warmer” and “colder”, but these are randomly placed across the buttons and do not actually give directional prompts to the user. The idea behind this is that via Wills we recognized that not only are we attached to the speed of a machine, but also rhetorically we have a deep trust that we should believe what the machine tells us. The best way to navigate through the correct prompts in our game is simply by starting on one side and systematically pressing all the buttons. The interesting part for us is that the most efficient way to navigate our game is through an algorithm, and success means that our digital other will speak back sentences from literature about our embodiment. This whole process looks to blur the line and confuse the user. A machine that has multiple prompts that cannot be relied on and also imparts poetic wisdom through algorithmic interaction challenges the idea of human computer interaction at its core. Our cabinet essentially lies and the user must engage and spend a considerable amount of time trying to figure out that this happening. This is anti-speed technology. To uncover the secret of our “game” the user must get to the point of frustration, must realize that the technology is not meant to help, that it simply is. We hope that this realization will prompt introspection making our project an object that users can think with.

One of the most difficult concepts found in the writing of Bernard Stiegler is encased in the Greek word Pharmakon; translated literally as the illness and the cure. The difficulty arises in the interpretation of this word because there is no direct English equivalent that signifies that something both is and is not, that it exists in a state of duality. Stiegler, in his investigation of the origin of mankind- in terms of the moment when we became tool-using animals- allegorizes this concept by using the Prometheus and Epimetheus myth. Stiegler is trying to make apparent the fact that the moment that our ancestors reached out and used tools “repetitively” we became something else; what we became is debatable. For Stiegler, this was the moment we became human, coincidentally, this is also the moment we understood our own mortally. Stiegler engages this concept through the myth, describing how once we were given the fire that belonged to the gods (from Prometheus) we recognized our mortality because we knew we were not immortal like the gods whose fire we were using. This interplay between technics and mortality is where we find the idea of the pharmakon. Our humanity is technical, an extension of our physical selves, but it is also organic, in that we must all recognize and face the possibility of our own deaths. These allowing conditions of humanity complicate our understanding of what it means to be human. One question that I ask specifically is this: If the fundamental moment of becoming human is through repetitive tool use and a recognition of our own mortality, then could it not be possible that other creatures at least have the potential to become human?

Difficulties of the concepts aside, these ideas apply nicely to our cabinet project. We have encased a recognizable object–Cameron’s moving image– in a box that the user must engage with and manipulate. Our intention is that by seeing a human likeness (distorted but recognizable) and interacting with it, that our users will be engaging in both repetitive tool use which extends outwards from the body and in a type of recognition scenario that astute users will hopefully understand to be a recognition of an entity that in theory (with enough power) could be immortal. This is how we engage Stiegler in our project, and how our cabinet is also a Pharmakon- it is a game and its solution, a representation of humanity, and an investigation into the handcuffs of immortality.

With all of our group members now finished presenting their seminar presentations for ENGL 794, we can now shift our attention directly to our final Kunstkabinett project.

Having received feedback regarding our initial video and future plans, we have made some changes that will allow us to not only complete our project in the alluded time but also allows to exemplify particular course concepts more fully.

Our first change to our project comes with the name of it. While “The Odyssey” was fitting with our “Nobody” character inside the cabinet, it really has no relation to our project beyond that. We are currently trying to come up with a new title which better suits our project (“Nobody’s Home” or something witty like this perhaps). We have decided to keep our avatar/being/cyborg character inside the cabinet named Nobody as we quite enjoy the effect that it brings to our project.

Secondly, we regret that we have decided to disable the eye movement feature we had initially intended to have in our project. As we were thinking with a “sky is the limit” attitude for our video project, we realized that implementing this feature in the actual cabinet would be much more technically challenging. As a result, users will now only have the ability to “control” Nobody’s head movements and speech functions.

The actual program for our project has been finalized as well. Users will be greeted with a classic arcade style splash screen that will ask them to “press start” much like an arcade video game would. Upon doing so, the splash screen will fade and users will be face-to-face with Nobody. With essentially no interface and little instruction as to what user’s limitations are when interacting with the cabinet, they will be left to explore the cabinet and its workings. The goal is for users to key in a proper sequence of words that will allow Nobody to utter a phrase. Essentially, a button on the control panel of the cabinet is assigned a word which starts the phrase. Users will then use trial and error to detect where the next word in the phrase is. Along the way, they may encounter various obstacles, complications or frustrations. These will make the goal of having Nobody speak more difficult. Once the user successfully keys in all of the words of the phrase (in order), Nobody will speak the phrase uninterrupted to the user. The buttons will randomize again and another phrase will be given for the user to uncover. We have approximately 16 phrases at this stage, which we expect will be more than enough for the purposes of this project. The phrases we have decided to include stem from various realms including literature, religion, and even iconic figures. While these phrases comes from different areas, they all have a relation to our projects central theoretical foundations. More on that later.

We will be using the same visual technique as our video for users to interact with. I will assume the character of Nobody and the filming process will begin shortly. One can expect much the same as our video in terms of cinematography. We may decide to alter it slightly for our final iteration, but that remains to be determined.

Finally, with regards to the theory that our project embodies/challenges, we have narrowed our focus to the major concepts of language, prostheses, and faciality. These are the central aspects that our project utilizes as its foundation, however, their are many other theoretical connections that can be drawn from these central concepts. Keeping the notions of language, prostheses, and faciality in mind when engaging with our project will be essential to our users. These concepts can be found in some of our previous blog postings, but will be elucidated with specific regards to our project in the presentation of our cabinet. We will also outline other connections to course concepts that our project touches on later once we have a complete picture of all the concepts we have worked with in ENGL 794.

Stay tuned for upcoming progress pictures, late breaking developments, and other important information pertaining to our project!

In Robert Mitchell’s “Bioart and The Vitality of Media”, particularly in the section ‘Affect and Framing I: Readymades’ in his chapter ‘Affect, Framing, and Mediacy’, he provides a useful introduction to vitalist bioart which appears to work well with our cabinet project. Mitchell states that “understanding the experience of bioart in terms of affect also allows us to focus more closely on the ‘artistic’ conditions of possibility of contemporary vitalist bioart-that is, the ways in which recent vitalist bioart depends upon twentieth–century techniques of framing objects and experiences as ‘art’ in order to prolong experiences of affect. This is an important aspect of vitalist bioart, for it is intended not simply to produce but also to prolong experiences of intensity. This goal distinguishes recent vitalist bioart from other experiences which may produce affect through a sense of becoming-a-medium…Vitalist bioartworks, by contrast, seek to extend the experience of affect rather than allowing it to resolve into situated perceptions and cognitions” (77). In order to fully understand what is meant here by Mitchell and to form some sort of connection with our cabinet project, a definition of vitalist bioart is useful. Mitchell says ““Vitalist bioart is… primarily exploratory and experimental: that is, rather than seeking–or seeking to safeguard–the ‘meaning of life,’ vitalist bioart instead explores what life can do” (32). Also in this section, Mitchell highlights a form of bioart that arguably our cabinet project falls into. “Readymade” is a term coined by Marcel Duchamp to describe the practice of reframing industrially produced (i.e ‘readymade’) consumer items, such as bicycle wheels, bottle-drying racks, and urinals (or in this case, a industrial arcade cabinet), within the space of the art gallery (78).

Our project essentially will exist as a readymade installation of vitalist bioart. As Mitchell clarifies, “the readymade suggests, does not preexist its exhibition in an artistic space; rather, the exhibition of something establishes its (possible) status as art” (78). While it satisfies the condition externally of a readymade, it functions much more than simply an object to be viewed. Indeed, the cabinet serves as a housing for a more intricate and interactive application (or perhaps art as it is being exhibited within the confines of an art gallery). While our cabinet itself is not actually a living, breathing, biological instalment, certainly an argument can for our “I Am Nobody” application contained within the cabinet. As it presents a way in which the body can be ‘altered’, more specifically, mediated, an exploration surrounding an aspect of biology is certainly on display. Our cabinet presents the head of a human, extended into the cabinet, and remediated through the interactive participation of those who engage with the cabinet. Whether or not gallery goers will be amused, view our cabinet as art, or just be down right annoyed with our installation remains to be seen. What we certainly hope to accomplish is to get participants thinking critically (otherwise, we would not be doing our job).