Having delivered my seminar presentation on Anna Munster’s Materializing New Media: Embodiment in Information Aesthetics, I want to point to some particularly relevant concepts to our cabinet project that Munster’s work contains. Rather significant to our project in particular is most of the information contained within Chapter 4: Interfaciality. The term itself can essentially be described as the interchangeability of various “faces” over a number of similar objects, people, or surfaces. Munster explains that “to [Camilla] Griggers, faces are everywhere: surfaces, monitors watching the subject or watching the subject being watched, the interchangeable faces of porn stars, supermodels and so on…Here we are, balancing precariously between the before and after face, the human and the technologically reconstituted face. We are caught between faces: interfaciality” (130). Important from this passage (at least for our purposes) is the notion that “faces are everywhere: surfaces, monitors watching the subject or watching the subject being watched”. As our cabinet will essentially be composed of surfaces (Plexiglas and monitor) as well as house a literal “face”, our project engages with this notion of interfaciality quite closely.

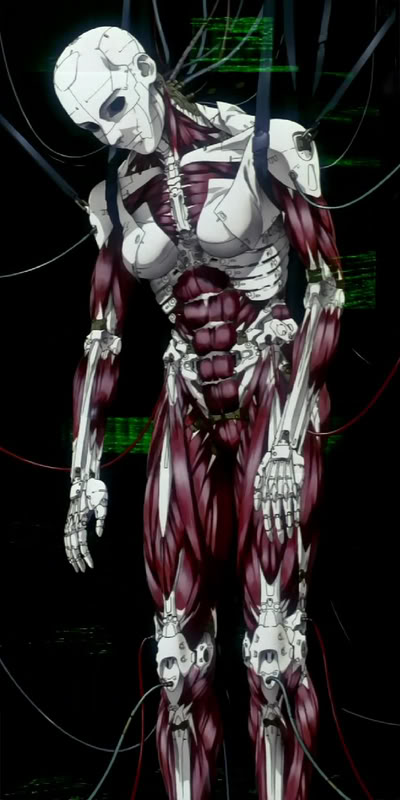

Moving into the chapter itself, other important concepts including “Faciality”, “Interface”, “Human-Computer interaction (HCI)”, and “Facialization” stood out with strong relation to our project. As Munster describes, “Faciality is a social aesthetic and technical machine that organizes corporeal engagement and representation into a relation of subordination to the face. The face, according to Deleuze and Guattari, has become a frozen structure in Western history and culture, perpetuating a cult of ‘personality’ and setting up exclusionary zones between surface ‘features’ and the depth of ‘mind’ that lies behind these” (21). This concept is directly applicable to our cabinet face “Nobody”, who will undoubtedly perpetuate a cult of personality and establish exclusionary zones between surface ‘features’ and the depth of ‘mind’ that lies behind these. While appearing to have the “depth of mind”, Nobody as an entity possessing a face will simply present surfaces features that would suggest something more that lies behind it.

Munster continues with important concepts, outlining that “the interface appears as a figure to rejoin what has already been separated out from and hardened against the flux of material existence. The machine is conceived as something that we confront across the void of the world and that we can only ever connect with through a ‘face to screen’ confrontation or communication” (47). I was particularly interested in the rhetoric employed in this definition and wondered: Is the ‘face to screen’ confrontation or communication the ONLY way we can ever connect to the machine? What is meant by “void of the world” that Munster uses to describe the apparent gap that we deal with in our interactions with machines? Perhaps the answers to these questions can be found in my peers or perhaps they will reveal themselves to me as our adventure in this course continues. Nevertheless, our cabinet will employ the above mentioned interface, but the face to screen confrontation will be complicated to include a face and controls that users will confront and/or communicate with.

Human-Computer interactions (HCI) are “computational design features [such] as the desktop, the Windows, Icons, Mice and Pointers interface design style and the development of early immersive virtual environments” (121). Munster expands her definition stressing that “the premises of HCI filter into and arrange our everyday engagements with digital technologies such as…sitting in front of a computer monitor and interacting with an interface intimates a certain form of bodily posture and gesture that is clearly demarcated. The ‘user’ greets or confronts a screen and thereby interacts with the ‘face’ of the computer; we are as much placed and used by this ergonomics as we are users in it” (122). Indeed users of our cabinet will no doubt be included within this system of interaction. What is important especially about this passage is the language the Munster uses that so exceptionally relates to our cabinet project.

The last concept that is particularly useful from this chapter in relation to our project is the notion of Facialization: “[it] is a system of codifying bodies according to the centralized conception of subjectivity or agency in which the face, literally or metaphorically, is the conduit for signifying, expressing and organizing the entire body. Because the computer also comes to figure as a ‘subject’ in HCI, it too takes on facialized attributes and qualities” (122-3). This concept is particularly important for us to consider as we have chosen literally a “face” to represent our cabinet. As the computer is figured as a ‘subject’ in HCI, with the addition of our “faced” Nobody, we may have taken the concept of faciality one step further. As our project approaches its completion, we will have a greater understanding about what these concepts mean for our cabinet. In the mean time, stay tuned and sit tight.

Also, please feel free to consider what I have noted as “Food for Thought”. Essentially, these were some questions or points of contention I came across when reading MNM:

“If one is using theory to catch up to the chameleon that is everyday life in relation to new media technologies, inevitably a sense of lag sets in” (23)

-What are we to make of the “chameleon” relationship between new media technologies and everyday life? Is lag in this sense “inevitable”? Why might Munster situate theory as having to “catch up”?

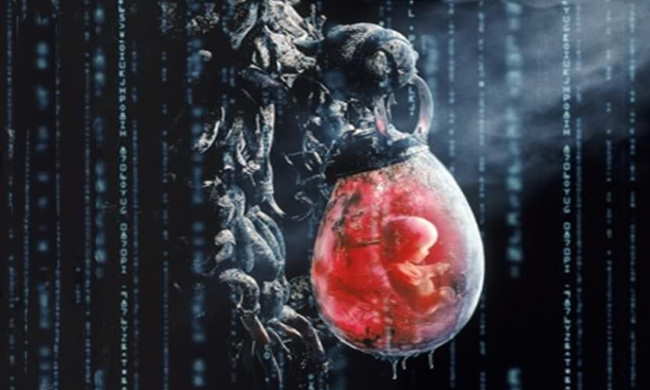

“‘CyberLife is concerned with the re-vivification of technology. Through CyberLive we are putting the soul back into lifeless machines-not the souls of slaves, but willing spirits, who actually enjoy the tasks they are set and reward themselves for being successful’” (125)

-As this quote is not directly from Munster and therefore we cannot critique her per se, what are we to make of this idea of “the re-vivification of technology”? Does soul here coincide with “algorithm” perhaps? Is this ‘goal’ or ‘mission’ that CyberLife puts forth logical or even reasonable?

“Roy Ascott, for example, has been at the forefront of this position on digital art, arguing that the computer is not simply a tool but an entirely new medium ushering in a novel visual language and producing new conditions for making and receiving the digitally produced artwork” (154)

-This may sound familiar to anyone who was in ENGL 793, but the question I have here is: Is the computer and entirely “new” medium? I know what I think, but I’m interested to see what others think of Ascotts assertion (and Munster’s apparent support for it as she does not challenge this notion).